David King: Designer, Activist, Visual Historian, Soviet Art Collector - by Rick Poynor (Book Review)

David King: Designer, Activist, Visual Historian, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2020, 240 pp.

In 2005, we suggested on the WSWS that David King—British artist, designer, editor, photohistorian and archivist—was “one of the more remarkable artistic-intellectual personalities of our time.” There is no reason, four-and-a-half years after his sad death in May 2016, to retreat from that assertion.

Rick Poynor, a frequent writer on graphic design and visual communication and founder of Eye magazine, a quarterly print magazine on graphic design and visual culture, has written a well-researched, sympathetic and honest book on King’s life work, David King: Designer, Activist, Visual Historian (Yale University Press).

The new volume is welcome and recommended to both those familiar with King’s art and design and those coming to it for the first time. In his preface, Poynor argues convincingly that what “we see in King’s body of work is a visual form of authorship grounded in mastery of his subject matter and pursued at the highest level.” He divides his book, complete with an immense and fascinating array of photographs, illustrations and other images, into three principal chapters—which follow a generally chronological order—that treat King’s involvement with “Visual Journalism,” “Visual Activism” and “Visual History.”

King had tremendous skill in many areas, but what made him so “remarkable” as an artistic personality, above all, was his concern with the burning social and historical questions of our time. In an obituary on the WSWS, David North argued that King, above all, had “devoted his extraordinary gifts as an artist to salvaging the historical truth of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and its aftermath from beneath the vast and now wrecked edifice of Stalinist crimes and lies.”

For his part, Poynor notes that to “understand what King was doing as a designer and author, and appreciate his work’s saliency, it is necessary to be interested in his field of study: the history of the Russian Revolution.” Of course, this was not an academic interest, but a concern with the Russian Revolution as the first great front in the world socialist revolution that would liberate humanity from capitalism.

Over the course of five decades, King applied his knowledge and artistry to a series of carefully prepared and substantive works, including Trotsky: A Documentary (1972); How the GPU Murdered Trotsky (1977); Trotsky: A Photographic Biography (1986); The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin’s Russia (1997); Ordinary Citizens: The Victims of Stalin (2003); Red Star Over Russia: A Visual History of the Soviet Union (2009); and Russian Revolutionary Posters: From Civil War to Socialist Realism, from Bolshevism to the End of Stalinism (2012).

There are also beautiful volumes or catalogues, which King wrote or designed, dedicated to the work of German visual artist John Heartfield, major Soviet artistic figures like Alexander Rodchenko and Vladimir Mayakovsky, Soviet and Mexican photographers, caricatures from the 1905 Revolution in Russia and more. If that weren’t enough, as Poynor sets out, King made extensive efforts as a poster-maker and album designer. In short, there is no comparable body of artistic-political work in recent decades.

If David King is not better known, it is primarily attributable to the shift to the right in so-called intellectual circles, their hostility to the October Revolution and their growing social indifference.

David North argued in 2016 that King “did not labor to subjectively impose a striking and eccentric form that would call attention to himself as an artist. What imparted to his book design such a powerful and genuinely original character was the degree to which the historical events reflected in the pictorial images guided the author’s presentation.”

In this regard, although his subject was the “cold” matter of history, King returned to the method and approach of the great classical artists. In a period in which a given artist’s subjective interpretation came to dominate so overpoweringly and the very notion of objective truth came under fierce attack, King continued to focus his attention on reality itself.

As King explained in a 2008 interview with the WSWS, he had begun 40 years earlier “collecting material out of an overwhelming interest in discovering the truth about what happened to the Russian Revolution and the Soviet Union. I wanted to uncover, through visual means, what happened, to collect visual evidence” (emphasis added). How many contemporary artists even speak in such terms?

His pursuit of historical truth inevitably led him to the figure of Leon Trotsky, the Russian revolutionary murdered by the Stalinist murder apparatus in 1940. King observed in our 2008 interview that in the late 1960s great interest suddenly arose “in Trotsky and one or two other figures, as major alternatives to Stalinism. There was a crisis, and people were looking for alternatives. I determined to find out what really happened to Trotsky, who he was.”

King was one of those intellectuals, few in number in our epoch, whose remarks in 2008 did not embarrassingly contradict those he had made 45 years earlier. Poynor cites King’s 1972 comment in an interview with Keep Left, the newspaper of the Trotskyist youth movement in Britain at the time, the Young Socialists: “Without a clear understanding such as that provided by Trotsky, the whole world can be ugly and unbearable, because all you see around you is either capitalism or Stalinist bureaucracy.”

“Though not a member of the Workers Revolutionary Party,” David North pointed out in his 2016 tribute to King, “which was then the British section of the ICFI [International Committee of the Fourth International], David greatly respected its theoretical work and political activity in the working class. He followed with enormous interest the investigation initiated by the International Committee in 1975 into the assassination of Leon Trotsky. He contributed his time and many photographs in his private collection to the design of How the GPU Murdered Trotsky, published in 1977.”

Writing of the latter work, Poynor comments that it “brought together 19 articles first published in the Workers Press, the daily newspaper of the Workers Revolutionary Party, which provided new information about Trotsky’s elimination by the Soviet secret police.” Building on his long experience, Poynor goes on, “King delivered probably the most ‘tabloid’ design in his oeuvre. … Each chapter begins with a headline in huge condensed capitals, centred, ranged left, or slanted. … King achieves a highly engaging balance between the images and the copious text: the magazine-like book looks urgent, weighty and exciting in its revelations.”

King’s decades-long effort to learn and communicate to the public “what happened” was eventually concretized in the massive collection of more than 250,000 photographs, posters, drawings and other items associated with the October Revolution and with Trotsky—most of which are now housed at the Tate Modern in London—he accumulated over nearly half a century.

Poynor’s book surveys the history and evolution of King’s print communications work in a comprehensive and conscientious manner.

|

By presenting examples of King’s most significant projects as a graphic designer, art director, visual editor, historian and writer—along with careful research about his life and career, including interviews with those who worked with him—Poynor successfully reveals the artist’s lasting contribution to graphic communications over nearly five decades.

In crafting an appreciation of King’s work, Poynor writes that he was a pioneer of a genre that later became known as the “designer as author.” However, Poynor explains that King was both ahead of this trend by two decades and its unique representative.

Whereas the 1990s “designer as author” school featured books written by graphic designers about their own field, King co-authored books about and became the foremost authority in the world on the photographic and graphic history of the October Revolution and the life and death of Trotsky.

Poynor had long recognized the significance of King’s work and been preparing a monograph about him when King suddenly died of a heart attack at age 73.

In the section of the book entitled “Visual Journalism,” Poynor briefly reviews the fact that as a youth King identified with left politics and was opposed to capitalism. Gifted with obvious artistic talent, King enrolled at the London School of Printing and Graphic Arts (LSPGA) at age 17 in 1960, seeking a degree in typography.

The radicalization among students in London no doubt played a role in King’s political and creative development. Poynor presents the poster artwork for a student protest during the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962) and a photograph of a large banner hanging in Trafalgar Square during a nuclear disarmament rally (1964), both designed by King.

The faculty at LSPGA were proponents of modernism in graphic design. As Poynor writes, “The visual thinking of the Bauhaus was a strong influence on the department’s teaching.” The school’s modernism in typography took the form of a strident use of sans serif fonts and, for King, this was the beginning of his career-long, signature use of the typeface Franklin Gothic Bold. Soviet Constructivism later became another significant influence.

Poynor is careful to explain that King “always resisted any suggestion that he was concerned with graphic style as such” and that “his visual style should be seen as a kind of handwriting—the way a personality expresses itself.”

Reflecting the utilitarian theory advocated in 1930 by the English typographer Stanley Morison—designer of Times New Roman—King told Creative Review in 1985, “I’m less into form than content. I’ve never been interested in typography for its own sake since I see it simply as a vehicle for visual communication,” adding, “The content of your work, assuming one has any interests at all, is what one should concentrate on.”

At the same time, Poynor shows that King’s design work “possessed some of the most recognizable ‘handwriting’ of any graphic designer who ever worked in Britain.” He goes on, “Aestheticism and politics were closely intertwined throughout the overlapping phases of King’s career and his content was embedded in a style of visual form that was both purposeful and eloquent on its own terms, as it needed to be, and a sure sign of his hand.”

Aside from his persistent use of a restricted list of sans serif bold typefaces, King also perfected the technique associated with Heartfield, the socialist visual artist and designer who used photomontage as a political weapon. Introduced to the German artist at LSPGA by an assistant lecturer, Poynor quotes King, “I suddenly realized what graphic design could achieve. … Seeing Heartfield’s work…had a fantastic impact on me.”

It was on the design staff of the Sunday Times Magazine, where King began working full-time in 1965, that these creative and graphic influences merged with his developing political and historical interests and resulted in some of the most significant visual journalism ever produced.

King designed a 10-page feature published in the magazine on October 8, 1967, that celebrated the 50th anniversary of the October 1917 revolution. The front cover of the edition contained a photomontage also designed by him. Both the cover and six of the 10 pages are presented in Poynor’s book.

The feature was titled, “A Dictionary of the Revolution” presenting topics in an “A to Z” arrangement with photographs and descriptions of each, like a mini-encyclopedia of the revolution. The opening main spread of the dictionary contains a large image of a poster called “Books” by Alexander Rodchenko from 1924.

Some historical context is important here in relation to King’s work on the Sunday Times Magazine. By 1960, the publication had reached a circulation of 1 million copies as a revolution in print technology was under way. Originally called the Sunday Times Colour Supplement, it was the first use of color in newspaper publishing in Britain.

These changes, along with the replacement of letterpress technology with photomechanical methods, greatly expanded the speed and design possibilities in newspaper production. Working with the others on the design staff, King applied his creative sensibilities and revolutionary political orientation to these developments.

While the 1967 feature on the anniversary of the Russian Revolution was extraordinary, Poynor explains that the Sunday Times published many other kinds of reporting including “crime stories, political and social investigations…no-expenses-spared travelogues, glitzy fashion spreads…and searing, unsettling photographic reports from the frontlines about war and famine.” King worked on many of these projects as well.

Given that most of the photographic material that King was working with was black-and-white, the availability of color posed some challenges. Here, Poynor discusses the Pop art techniques that King implemented to apply flat color tinting over black-and-white photos. King is quoted saying, “At the Sunday Times, mid-1960s to mid-1970s, it was more based on Pop art and popular culture things, even when it was political.”

Poynor includes an example of King’s original mechanical art with instructions to the printer for the different color techniques that were to be applied to a photomontage illustration for a portrait of the tycoon Howard Hughes that appeared in the Sunday Times in 1969 as part of a series called “1000 Makers of the Twentieth Century.”

What emerges from these examples is that King was very familiar with the details of the different printing processes used to reproduce his design work, whether it was screen printing, rotogravure or offset lithography.

Among the exceptional skills King possessed was the ability to see elements in a photograph that others could not see. According to several colleagues interviewed by Poynor, King had both the uncanny ability to select the right picture to use and how to crop it the right way. One coworker, Gilferie Lock, told Poynor that King knew “how to get the maximum impact” out of every photo. This exceptional ability is shown in an example from the Sunday Times in 1973. A photo-essay shot by famed photographer Don McCullin on the homeless called “Crisis on Skid Row” was designed by King.

All of the things that King learned from previous experience, along with a trip to Moscow in 1970, prepared him for a project at the Sunday Times that would transform him from a graphic designer into a visual historian. The publication on September 19, 1971, of a cover story about Trotsky included King as the designer as well as the lead picture researcher.

King wrote the captions for the photos that accompanied the 12-page pictorial survey called, “Trotsky: Conscience of the Left.” Although most copies of the printed edition were never distributed due to an industrial action at the production facility, some made it into circulation.

Around this time the editor of the Sunday Times, Michael Rand, suggested to King that he work with writer Francis Wyndham on a book that would later have the title Trotsky: A Documentary. As Poynor explains, the use of the term “documentary” was meant to suggest that this book of pictures of Trotsky was a dramatic biography “much the same way as a film uses a combination of image and sound.”

At the time of its publication, Trotsky: A Documentary, was received enthusiastically by Keep Left and Workers Press, the publications of the British section of the International Committee of the Fourth International at that time. King was praised in Workers Press for assembling “perhaps one of the best collections of Trotsky photographs and prints in existence.”

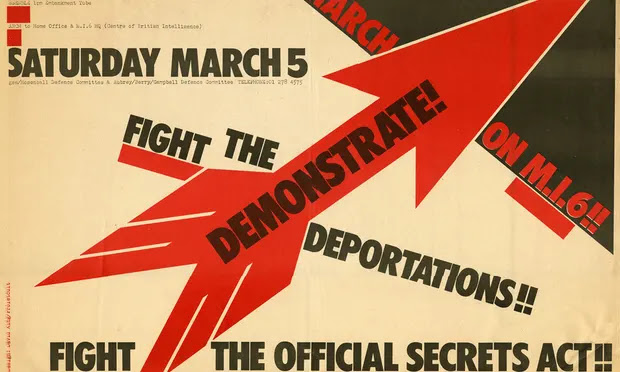

Poynor’s book follows King during the “second phase of his career, from around 1975 to 1990,” as a “visual activist.” King designed the covers of the series of works by Karl Marx for Penguin Books, he produced posters for a host of protest movements, including the Anti-Nazi League and various anti-apartheid groups.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 did not produce in King, who grasped the Trotskyist analysis of the Stalinist regime, the type of political and moral collapse that it did within wide layers of the middle class “left.” In his 2008 interview with the WSWS, King scoffed at the notion of “the end of history! Stupid stuff.” He went on, “The post-Soviet historians, like Richard Pipes, begin from the premise that there never was an alternative to Stalinism. That’s false. My collection also proves that the claim is false.”

If anything, King’s work became deeper and more substantial after the disappearance of the Stalinist regimes. The series of volumes he then produced, The Commissar Vanishes, Ordinary Citizens: The Victims of Stalin and Red Star Over Russia in particular, are imperishable contributions to historical knowledge and devastating blows to the post-Soviet school of historical falsification.

In regard to Red Star Over Russia, Poynor argues that the work “is a brilliant recapitulation of what King had been doing with pictures ever since his work for the Sunday Times. The flow of images feels so natural that it seems effortless. This is the art that conceals art.” (emphasis added).

He continues, “It is a book that could probably only have been conceived and executed by an author who is both a highly informed collector on a fabulous scale and an exceptionally skilled editor of pictures. While there is no reason why books should not be authored in this fashion, densely told visual histories on this scale, in printed form, remain the exception.”

Poynor’s new book, in its own fashion, assembled in a “highly informed” manner and “densely told,” is likewise an outstanding exception.

Comments

Post a Comment